Depression and the power of words

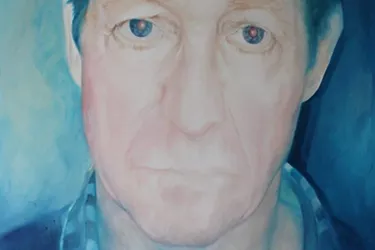

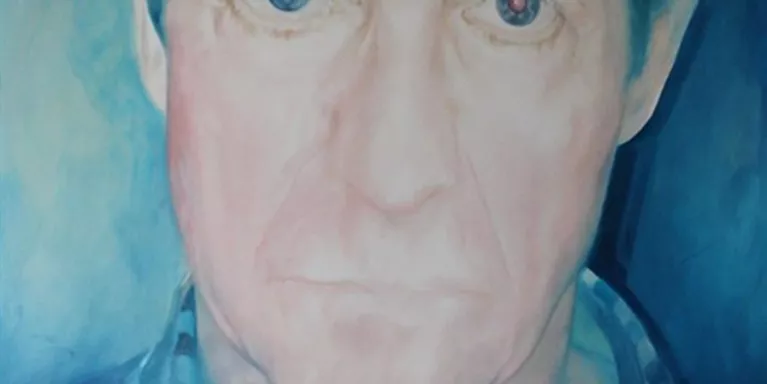

Ben Wilkinson blogs about the role poetry played in his fight against depression

‘A good poem gives us the words for what we feel, and rescues us from the inarticulate’.

About a year before I suffered with depression, I remember stumbling across this saying, by the American poet Richard Wilbur. It stayed with me even then – before I really understood it, and felt the truth of it. Before my life changed forever.

"I read and write poetry so that I can better understand myself and those around me."

I didn’t fully realise it back then, but I now see that I’ve always written poetry as a way of helping to explain things to myself. I read and write poetry so that I can better understand myself and those around me. I see poetry as a conversation. When I’m reading a poem, I’m in conversation with that poem and the feelings it provokes in me. When I’m writing a poem, I’m in conversation with myself, my hopes and fears, but also – I hope – with anyone who eventually comes to read it.

In late 2012, I lost sight of all this. I fell, bit by bit, into a state of anxiety and depression that gave me a single, unshakeable perspective of the world – that I was worthless, and that everything I did was a waste of time. Disillusioned with and consumed by work, feeling my self-esteem hit rock-bottom and with my personal life spiralling into complete turmoil, I fell into a state of inertia, and crawled into bed. I stayed there for weeks.

The most terrifying part of my depression was definitely that unwaveringly bleak outlook. The sunniest days, the smiles and laughter of others, favourite foods – nothing could shake me from a feeling of hopelessness and the thought that I had completely let down everybody I cared about. I’d never known anything like it, or thought I could ever feel so permanently dejected – thinking I’d be better off dead, and probably soon would be. I lost interest in everything, even the things I cared passionately about.

Unable to work, my supervisor signed me off to recover. Inevitably, I found myself with time on my hands. Time I would normally have used to read and write. But to begin with, I couldn’t. I couldn’t focus to read for more than a minute at a time. Never mind pick up a pen. For the first time in my life, gripped by crippling anxiety and darkness, taking solace in reading and writing for pleasure wasn’t an option.

So I took up running. I don’t know why, but after weeks of inertia I decided it was a good idea – or I decided it couldn’t hurt anyway, and nothing could make me feel worse. Eventually, I hauled myself out of bed one day, pulled on trainers and plugged in my earphones, and headed out. I’d never run before, but hurrying along to the lyrics of my favourite songs, I took to it quickly. Soon I was heading out three or four times a week to clock up a few miles, taking in the roads and rural edgelands of Sheffield. I was hauling myself out of the darkness, and thriving off the endorphin release, the heart-pumping kick of pushing myself to run.

Running got me much fitter, and started to give me my confidence back. Along with the right medication, running helped to control my feelings of anxiety and powerlessness.

But there was still something big missing. I knew I’d never get back to feeling like myself again, or come to terms with what had happened, if I couldn’t write through it. Again, I needed poetry to help fully explain things – both to myself and, I hoped, to others. Slowly but surely, I started to immerse myself in books again. Poetry collections, short stories, autobiography – they brought me out of myself.

I put together a collection of poems, some written before my depression, and some after I’d recovered from it. A collection that I hoped was truer and braver than my earlier attempts at writing, and one that might touch on shared feelings, common experiences. I entered it for a competition, judged by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy, and to my surprise, it won.

Now don’t get me wrong, it was very exciting to see a little book of my poems published – to see my name on the cover. But the best thing by far was the response I got once it started to find its way into people’s hands. When people got in touch to say they really felt and understood what particular poems were trying to express, it reignited my belief in the power of poetry – to reach out and to speak to others, to strangers, simply by expressing a shared experience in a memorable way.

"I wanted the poem to be about holding on – about keeping that shred of belief, even in the worst moments."

In my poem ‘Hound’, I wanted to make use of the iconic image of depression as ‘the black dog’. But I wanted to show it in a different light – as an imaginary creature that can be defeated, and will come to be defeated, time and again. I wanted the poem to be about holding on – about keeping that shred of belief, even in the worst moments of clinical depression, that things will get better. Because they will, and they do.

I reckon poetry can sometimes be a way of imagining the very worst, even a way of facing up to it – using words as a kind of weapon. But I also think poetry shows us how to use words as a shield, to help protect us. If ‘Hound’ can offer even the slightest defence against the black dog, when it comes after me, you, or anyone else, then I’ll feel like the poem has done its job.

Hound

When it comes, and I know how it comes

from nowhere, out of night

like a shadow falling on streets,

how it waits by the door in silence –

a single black thought, its empty face –

don’t let it tie you down to the house,

don’t let it slope upstairs to spend

hours coiled next to your bed,

but force the thing out, make it trudge

for miles in cold and wind and sleet.

Have it follow you, the faithful pet

it pretends to be, this mutt

like a poor-man’s Cerberus,

tell it where to get off when it hangs

on with its coaxing look,

leave it tethered to a lamppost

and forget those pangs of guilt.

Know it’s no dog but a phantom,

fur so dark it gives back nothing,

see your hand pass through

its come-and-go presence,

air of self-satisfied deception,

just as the future bursts in on

the present, its big I am, and that

sulking hound goes to ground again.

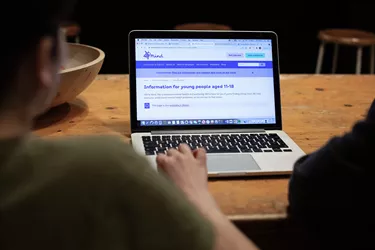

Information and support

When you’re living with a mental health problem, or supporting someone who is, having access to the right information - about a condition, treatment options, or practical issues - is vital. Visit our information pages to find out more.

Share your story with others

Blogs and stories can show that people with mental health problems are cared about, understood and listened to. We can use it to challenge the status quo and change attitudes.