We've come so far, but got so far to go

Stigma and misunderstanding often prevent people from seeking help in the early stages of mental illness. Juliette blogs about why it's time to change negative attitudes.

I recently heard a news report about how A&E staff respond to mental health crisis cases. Examples included one woman with severe depression who was told to “go have a cupcake” with her mother. Another suicidal woman was advised, “Sleep it off. It’ll be fine in the morning.”

What if these had been physical illnesses? I appreciate that modern A&E departments exist in a state of underfunded chaos. But if a man came in dying from blood loss, you wouldn’t tell him to have a slice of Battenberg. You’d calm him, reassure him and get him the urgent medical attention he needs to survive.

I started thinking about my own experiences and realised how far we’ve come — and how far we have yet to go — in handling, understanding, and caring for mental health conditions.

When my family GP first suggested I might need to see a psychiatrist, my parents weren’t keen. This was the early 90s; therapy wasn’t the done thing, particularly not for the likes of our family. Besides, it was only weight gain and OCD symptoms. And I was only eight years old. What does an eight-year-old have to worry about, right? This compulsive overeating, this anxiety, these daily rituals that I had to observe without fail lest I have a full-blown panic attack, like drying my hands so hard they bled, this was just a phase. I’d grow out of it.

I did grow out of that phase. But the illness shapeshifted into a depression and obsession with losing weight. By 14, I was diagnosed with anorexia and bipolar and then came another experience of stigma. I lost a lot of friends around that time. They were scared to see what I was doing to myself. I understand. I was scared too. Sometimes I still am.

“After my first hospital admittance, I wasn’t allowed to return to that school.”

The attitude of the educational establishment I was attending at the time could be considered a stigma. Certainly a lack of awareness and understanding. My school’s idea of pastoral care was to have a matron watch me eat cereal while the other girls were playing sports. After my first hospital admittance, I wasn’t allowed to return to that school. My mother was heartbroken; it must have felt to her as though the school had turned their backs on us. I don’t remember feeling a thing. I was numb. I suppose the school was scared too, scared my sickness might infect the others.

Even in treatment, I know many who have experienced shocking stigma. My first psychiatrist laughed at me when I told her I didn’t want to eat. I told her I was overcome with anxiety when I had to get my lunch, and I wished someone else would just order and collect it. She laughed and said it sounded as though I wanted a white knight to ride over the horizon on his mighty steed waving a baguette in the air. From that moment on, I promised myself not to open up to a medical professional in any real way again.

After 10 years of keeping that promise, I thank my lucky stars. I eventually found therapists who not only accepted and understood but had actually been through similar experiences themselves. Textbooks can’t teach you what real empathy can.

“When I was sectioned, those closest to me struggled with their own perceptions of mental illness.”

Back in 2002, when I was sectioned, those closest to me struggled with their own perceptions of mental illness. Constantly, I heard, “Why don’t you just get a grip?” “Why are you doing this to your family?” “Your mother loves you; why won’t you try for her?” I was “selfish”, “attention-seeking”, “making a fuss over nothing”.

These attitudes hurt. When you’re drowning, you don’t want the people on the shore to say you should kick your legs a bit harder or that you should stop mucking about in the water. If they did, it would feel as though you should stop calling for help. Just take a deep breath of water and let the ocean envelop you. Just give up.

When I flipped from anorexia into compulsive overeating, I became suicidal. That sounds almost like a career choice, right? “BECAME suicidal”. Like I became a journalist. But being suicidal didn’t feel like a choice. It feels like it is the obvious and only way forward. The only pathway to solving the unsolvable.

One night I was ready to take my life. In desperation, I went to my local A&E and told them I was going to kill myself. They offered admittance to the hospital’s psychiatric ward. I was desperate, so accepted.

The ward seemed to be a dumping ground: a place for all the crazies to collect. I saw no differentiation between eating disorder sufferers, alcoholics, depressives, people who heard voices. We were all in hospital beds in a dark room, crying, shouting, suffering. I had told the A&E staff that I couldn’t stop eating – I was beyond desperate. I had been locking myself in my bedroom for weeks, with a bucket for bodily functions, terrified of what I then viewed as my lack of self-control. I had been eating all day and night for weeks. I would pass out from the pain of eating and start again when I woke up. I had no idea what was happening to me, where I – who I was – had gone because my behaviour was not my own anymore. I was powerless over my illness.

And yet, on this ward, I had full access to a kitchen full of cakes, biscuits, jars of sugar. Well, they were full the night I arrived. After a night of being unsupervised in that room, I felt more desperate than ever. My heart was as empty of hope as the biscuit tin was of custard creams.

“I’ve slowly surrounded myself with people who understand and accept my mental health conditions.”

Over the years, I’ve slowly surrounded myself with people who understand and accept my mental health conditions. In fact, they are the kinds of awesome people who accept all kinds of things they maybe don’t have personal experience of. They have helped teach me how to handle my conditions in ways I may not have learnt alone.

And yet, there are occasions when I still encounter misunderstanding or ignorance.

I’m often asked, particularly in press interviews, “When did you get better?” To which I usually reply: “It’s an ongoing journey.” I still struggle. Even though I’ve been called “the picture of health” in articles, I still have days when I physically cannot leave the house and struggle to get out of bed. Those days when getting from the bed to the shower feels like hiking over the Himalayas. I have those days when I cry and cry. Why? I’ve no idea. For everything. For nothing.

Every day, even today, as I sit here writing this now, I struggle with food.

Feeding myself in a sane and level-headed way doesn’t come naturally. I have to force myself to think about it, to feed myself carefully and to consider every mouthful.

Early intervention in eating disorders has a higher rate of recovery, full recovery. Sadly, stigma and misunderstanding prevent people from seeking help for themselves or their loved ones at those critical early stages.

Suicide is the number one cause of death in men under 35. Perhaps if there was less stigma and more compassion, particularly in places like A&E, that statistic could change for the better.

I’ve written for Standard Issue and other sites about Twitter abuse I’ve received recently, choice comments such as: “mad harpy”, “crazy, why would anyone listen to you”, “definition of insanity”. I was told to “get off your ass or get some meds”. I was told I was “attention-seeking”.

I hadn’t realised these same attitudes towards mental health still existed. And do you know what? A part of me believed them. I was back to being 14 again and told the fault was mine entirely.

For me, the worst stigma is self-stigma. In the past few months, I’ve realised how much I still judge myself for my mental health conditions. Every day I say to myself, “Pull your socks up”, “get a grip”, “you’re letting everyone down”, “why can’t you just be normal?”

I’m never going to escape those voices. This stigma is so ingrained that often I don’t even realise I’m doing it until I encounter it from someone else. That’s when I realise that I’ve been an ignorant feckwit to myself for far longer than these guys have been. I wouldn’t ever talk to anyone else the shitty way I talk to myself. So why do I?

Because it’s easier repeating the same mistakes, treading the same path in my mind. It’s easier beating myself down and brushing the pain aside with a careless comment. It’s easier to pretend that just because you don’t see it, it isn’t really there. That pain I feel? That’s just my imagination. Go sleep it off… Have a cupcake.

But the pain is real. It’s desperately real. And if I ignore it, if we ignore the pain of others, we’ll be alone. And loneliness is a killer.

Information and support

When you’re living with a mental health problem, or supporting someone who is, having access to the right information - about a condition, treatment options, or practical issues - is vital. Visit our information pages to find out more.

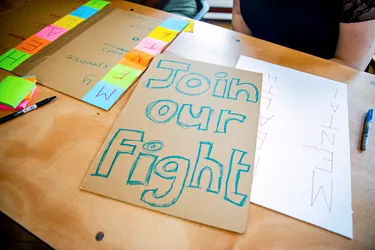

Share your story with others

Blogs and stories can show that people with mental health problems are cared about, understood and listened to. We can use it to challenge the status quo and change attitudes.